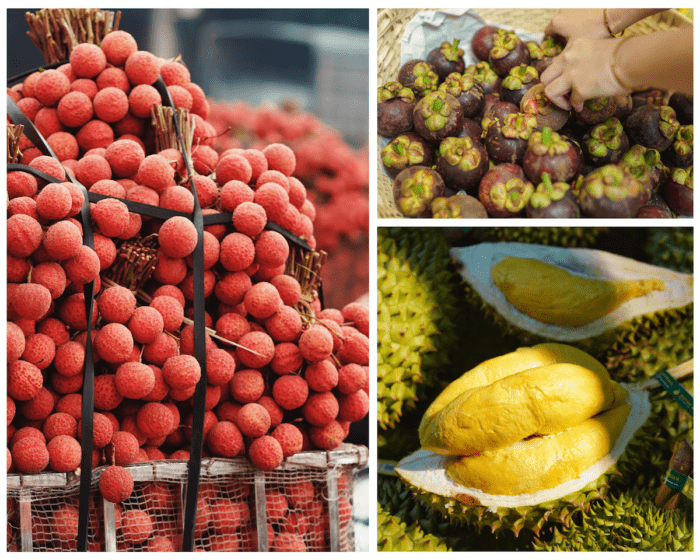

Selling lychees is like a race against the sun, said Nguyen Thi Minh Thuy, the director of Luc Ngan Xanh Cooperative who hails from a family of lychee farmers.

Farmers have to sell all their lychees by noon, or risk the fruit going bad from the heat. This sometimes means having to let go of their lychees at low prices.

Indeed, the laborious job does not always yield huge returns. Farmers begin selling lychees at 5am but the actual work—picking the fruit, plucking off the leaves and bundling them up—starts hours before that.

Farming is a huge pillar of Vietnam’s economy. In 2020, nearly 40 per cent of the country comprised agricultural land. Agriculture, forestry, and fishing make up about 12.6 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product in 2021, with the agriculture sector contributing to about 29 per cent of total employment.

But Vietnam’s agricultural industry is also dominated by small-scale farmers; the average farm size is less than a third that of Thailand or Cambodia.

And when Covid-19 hit, the pandemic exposed many vulnerabilities in Vietnam’s supply chain for traditional farmers.

But Vietnam’s agricultural industry is also dominated by small-scale farmers; the average farm size is less than a third that of Thailand or Cambodia.

One of the biggest constraints for these farmers is digital illiteracy, which limits their ability to acquire information, communicate and diversify their distribution channels.

They were unable to get direct access to the market to reach the end-consumer. Instead, they rely on several tiers of middlemen within their supply chains to get their agricultural product to the market and onto tables.

Thuy recalled the hardships her father had to endure as a farmer due to the lack of distribution channels.

“Till now, every time I see a lychee seller on the street waiting for a trader and then being pressured to sell their products at a lower price, I still shed tears,” said Thuy.

Such challenges faced by the farming sector spurred Thuy and her counterparts to set up Luc Ngan Xanh Cooperative.

Digital illiteracy limits their ability to acquire information, communicate, and diversify distribution channels.

Cooperatives like Luc Ngan Xanh tap Grab’s tech and wide network to connect with merchant-partners on the platform.

This allows the farmers to diversify their distribution channels and gain access to a more stable supply chain. Buyers can benefit from the access to quality fresh fruits delivered right to their doorsteps.

Farmers were also able to take advantage of the local demand for fruit, with a focus on young families and urbanites in metropolises Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi.

Bringing the ‘Fruitival’ to consumers

From May to October this year, consumers in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi can order high-quality, seasonal fruits such as durians, mangoes, avocados, lychees and mangosteens through GrabMart.

“Farmers don’t have the time, and don’t know how to tell the story about their products,” Thuy said.

Grab has allowed them to do that, she added.

In the last year’s edition of the Fruitival campaign, Grab supported the consumption of more than 100 tons of specialty fruits through its platform and ecosystem.

Upskilling for better farming

The Fruitival campaign is part of a broader programme we call GrabConnect. Launched in 2021, it’s focused on boosting consumption of farm products and promoting digital transformation within the farming industry. This is also in support of the country’s National Digital Transformation Programme for 2025.

Beyond selling on Grab’s platform, it was crucial to equip farmers with digital skills.

Last year, for instance, we provided offline training workshops to over 800 agricultural cooperatives across Da Nang, Can Tho, Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City. These workshops allowed farmers to learn more about digitalising and diversifying their sales channels.

3 Media Close,

Singapore 138498

Komsan Chiyadis

GrabFood delivery-partner, Thailand

COVID-19 has dealt an unprecedented blow to the tourism industry, affecting the livelihoods of millions of workers. One of them was Komsan, an assistant chef in a luxury hotel based in the Srinakarin area.

As the number of tourists at the hotel plunged, he decided to sign up as a GrabFood delivery-partner to earn an alternative income. Soon after, the hotel ceased operations.

Komsan has viewed this change through an optimistic lens, calling it the perfect opportunity for him to embark on a fresh journey after his previous job. Aside from GrabFood deliveries, he now also picks up GrabExpress jobs. It can get tiring, having to shuttle between different locations, but Komsan finds it exciting. And mostly, he’s glad to get his income back on track.