Why and how do ride fares on Grab change with time?

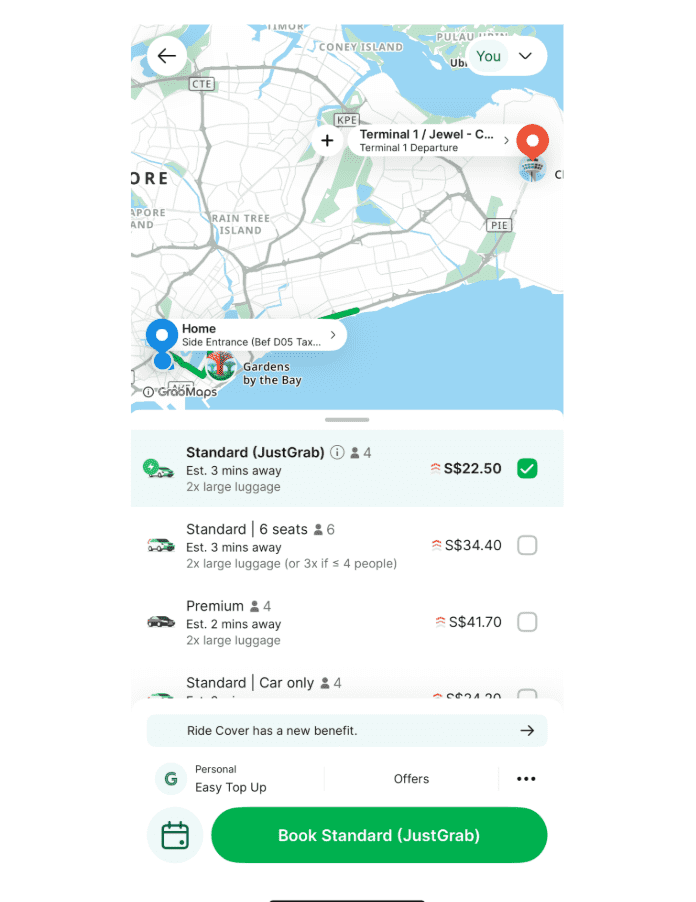

When you open Grab to search for a ride, the app shows a list of fares for the trip. Simple, right?

But HOW does Grab set the price for each ride at a given time?

Frequent ride-hailing users know that prices, even for the same trip, can vary—depending on factors like time of day, weather conditions, holidays or major events. Prices go up when there’s a spike in demand for rides, for example during rush hour.

Setting fair fares is a surprisingly complex problem. It requires a massive, real-time calculation with many factors.

In the following, we’ll explain some of the considerations that weigh into the calculation, and why we choose dynamic pricing on Grab.

What are the foundations of dynamic pricing?

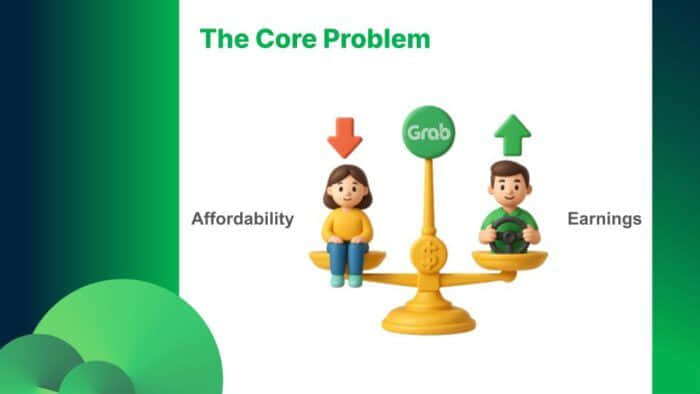

At its heart, transport is a marketplace with two equally important sides: Passengers and drivers. However, they have competing interests.

Fair prices are about balancing affordability and reliability.

If the price is too high, passengers will look for other options. Drivers lose a potential job. If it’s very low, this may seem attractive for passengers at first. But if the fare is not worth the drivers’ time, they will not accept the booking. This leads to long waiting times and an unreliable, frustrating experience for passengers. In other words, the cheapest fare is not the best, because it means fewer drivers are interested in the job.

What we need is a perfect balance: an attractive price for passengers that’s fair to drivers.

This price balance is not static, it changes with the pulse of the city. Rush hour, sudden downpours, major holidays or events, or even where the trip starts and ends, may shift the equation. That’s the fundamental challenge of dynamic pricing!

What are the basic components of a dynamic price?

The final price of a ride is calculated from several components.

There’s a fixed element, a base price based on trip distance and duration.

Then, there’s a dynamic component, a multiplier that adjusts the fare according to real-time market conditions. Simply said, if there are far more passengers than drivers in the area, the multiplier goes up. If there are plenty of drivers, the multiplier stays low, keeping the price close to its base level.

On top of this, there might be additional fees and surcharges: Tolls, platform fees, etc.

Let’s illustrate the purpose of the multiplier with two basic scenarios:

Classic oversupply

Mid morning in a residential area. Morning rush hour is over. We have plenty of drivers online and looking for a job, but few passengers need rides at this hour.

The system sees the imbalance, and tries to keep the dynamic price multiplier low to make the fare attractive and stimulate activity: We want the few passengers looking for a ride right now to go ahead and book.

Classic undersupply

The opposite is an undersupply scenario: Picture 7pm on Friday, when everyone wants to get home or go out for dinner. Few cars are available, there’s a supply crunch leading to long waiting times. The multiplier goes up. This has three effects: It tempers demand slightly: those who can wait past rush-hour might just wait and book a ride at a later time, or find an alternative transport option. But a higher price also incentivises drivers to accept bookings, and it incentives drivers to drive towards the high demand zone.

Price is a tool to rebalance the marketplace. And the multiplier is what nudges the price up or tries to keep it low.

How do we calculate the multiplier?

Of course, in the real world, demand and supply fluctuate in a more messy, complicated way. Identifying the fairest multiplier at each given moment—that’s where all the cool data science magic happens.

It’s too complex to spell out the entire equation, but let’s look at some of the foundational principles.

For example, we must make sure that we:

- Measure the right data as inputs for our calculations. How do we measure supply and demand in real time?

- Apply solid forecasting models so we can plan into the future and adjust, instead of reacting to what’s already happening

- Take into consideration regulations and other constraints that could impact the final price

Measuring the rights things

Measuring accurately is key. For example, how do we even determine supply at any given time? It’s not enough to count all the driver-partners online right now in a specific area.

We developed a metric that looks at how many driver-partners can fulfill bookings in the area in the next time window. This metric takes into account all drivers online and ready to accept orders right now, PLUS the drivers coming online within the next short time window, PLUS those about to finish jobs nearby, MINUS drivers that might choose to go offline in the same time window. This gives us a more accurate picture of true supply.

Demand must also be estimated correctly. What counts as demand? Does each time a passenger checks the fare on their app count as a demand signal? Or only when they go ahead and book? Over-or undercounting demand leads to bad pricing decisions.

We came up with metrics that bundle different fare checks or booking attempts for the same trip intention within a certain time window into one. That gives us a cleaner signal of how many distinct trips passengers are considering.

This process has similarities to the way we measure website or app engagement. Popular metrics like Unique Page Views or Monthly Active Users are also born out of the attempt to track the most useful, accurate signals.

Forecasting and adjusting

Here comes the most exciting part about our fare calculation. Because we collect good data, we can make projections into the future.

In fact we do this in a continuous intelligent loop. We calculate the ideal sequence of multipliers for the next ten minute window for each area, and apply the decision for the first minute.

Then, we get new real-time information based on that decision, and the time window moves forward, calculating the new next ten minute projection that includes updates, if there are any. We predict, act, and course correct in a constant cycle.

This moves us from adapting our prices reactively, towards anticipating what demand and supply will realistically look like in the near future.

We can use price as an instrument to subtly rebalance the marketplace. This increases the reliability of the platform because we can incentivise drivers to move towards high demand areas before a crunch happens.

But wait, there’s more

As we already said, the real world is messy. Many more considerations flow into our fare modifier calculation. We can’t list them all.

But understanding the foundations helps grasp the complexity of dynamic pricing.

For example, another nuance comes from price laddering: Fares for all types of rides—for instance, regular vs premium rides—need to shift in relation to each other, in a way that makes sense.

There are also certain constraints. For example, prices can’t jump from 1x to 3x in a minute—that would put passengers off. We make sure prices remain consistent, and that passengers do not experience sudden price shifts when checking for the same trip within a short period of time. Additionally, there may be regulatory restrictions on overpricing or underpricing rides.

We also strictly do not apply price discrimination, meaning that we do not adjust fares based on individual spending behaviours of passengers or driver-partners.

The final price our dynamic pricing system comes up with represents the best solution within the given constraints.

So, the next time you wonder about why prices on Grab show up the way they do: Now you know!

3 Media Close,

Singapore 138498

Komsan Chiyadis

GrabFood delivery-partner, Thailand

COVID-19 has dealt an unprecedented blow to the tourism industry, affecting the livelihoods of millions of workers. One of them was Komsan, an assistant chef in a luxury hotel based in the Srinakarin area.

As the number of tourists at the hotel plunged, he decided to sign up as a GrabFood delivery-partner to earn an alternative income. Soon after, the hotel ceased operations.

Komsan has viewed this change through an optimistic lens, calling it the perfect opportunity for him to embark on a fresh journey after his previous job. Aside from GrabFood deliveries, he now also picks up GrabExpress jobs. It can get tiring, having to shuttle between different locations, but Komsan finds it exciting. And mostly, he’s glad to get his income back on track.