The coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc on food merchants across Southeast Asia, exposing fundamental weaknesses in the food and beverage industry. Online delivery platforms like Grab continue to help, but are not a substitute for rethinking the path to profitability for food merchants across the region.

Covid has hurt Southeast Asia’s food and beverage industry

The past two years of Coronavirus pandemic have hit the economies of Southeast Asia hard, as job loss, international supply chain issues, restrictions on movement and slowdowns in key industries like tourism have resulted in lowered growth estimates for the region.

These effects have been strongly felt in the food and beverage industry, where the drop in sales has shrunk the market an estimated 20-35 percent, leading to large scale closures and job loss. In Singapore, sales in the food and beverage industry dropped 26 percent from 2019 to 2020, the worst such change since 1986 when data was first compiled.

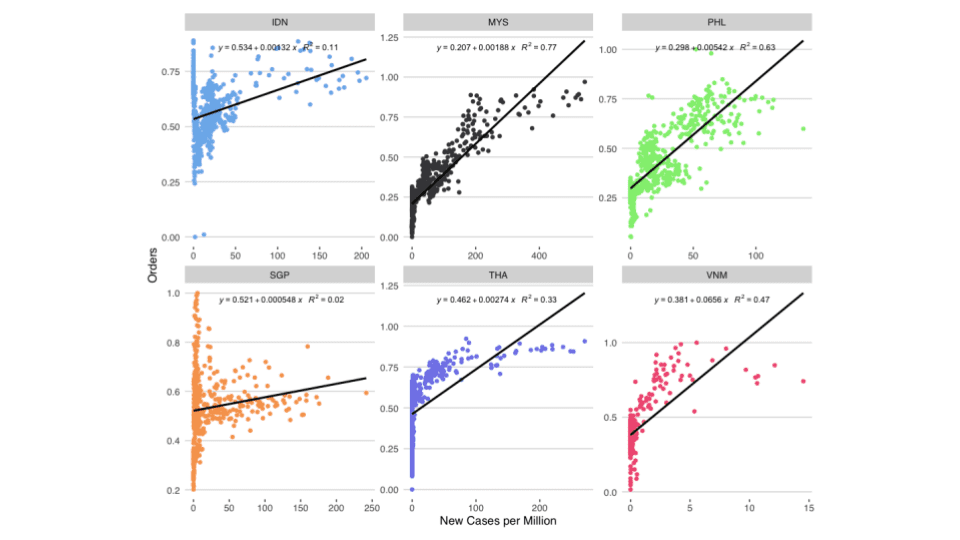

Figure 1: Plot of food delivery orders against new covid cases per million (Vietnam imposed delivery restrictions from 09 Jul 2021 onwards resulting in 0 deliveries–we have excluded that data from this graph). Source: Grab and Our World in Data.

A glance at the trends in order volume across six Southeast Asian markets (Figure 1) confirms that when new daily Covid infection rates are higher, food orders passed through Grab’s platform also tend to be higher.

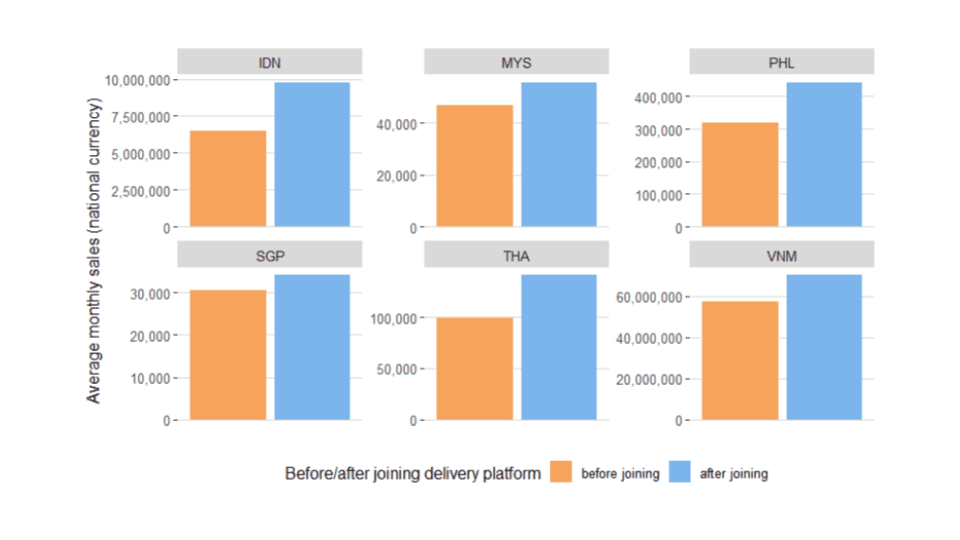

There is some evidence to suggest that food delivery platforms gave merchants a much-needed lifeline as dine-in sales dropped during the pandemic. An August 2020 survey of food merchants on delivery platforms found that even several months into the pandemic, average monthly sales (accounting for both before- and during-Covid sales for the 70% of merchants in the sample who joined a platform before Covid) were higher than before joining the platform (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Food delivery sales across any delivery platforms for merchants (excluding large chains) before and after joining Grab. 30% of the sample are merchants who joined Grab from April 2020 onwards. Source: based on a survey conducted during the Covid pandemic (August 2020) among 600 merchants by Cardas Research Group.

…but food delivery is not a panacea for issues within the industry

Despite platforms like Grab providing an effective way for food merchants to grow their businesses during uncertain times, the pandemic has laid bare the issue of profitability within the industry, for which online food delivery by itself cannot be an adequate response.

Even before the pandemic, food and beverage businesses tended to operate on slim margins, marked by high and rising costs such as rent, labor and food goods. For example Vietnam had 8.8% year-on-year growth in average labor costs from 2015 to 2019, an increasing trend echoed in Laos and Indonesia over the same period. In Singapore, one pre-pandemic inquiry estimates that 75 to 78% of food service operating expenses were accounted for by rent and labour costs. These factors make merchants particularly vulnerable to shocks, such as sudden fluctuations in demand, brought on by covid or other factors.

To remain profitable and to reduce these vulnerabilities, food merchants need to control costs while building economies of scale. Online deliveries act as an additional revenue stream to offline dining, allowing food merchants to increase sales without putting as much pressure on fixed costs like tables or dining space.

But the cost structures of dine-in and delivery businesses are not the same, and the challenge to profitability can be exacerbated when the mix of online orders evolves beyond what a merchant’s business model was originally designed for. For example a merchant may have a high fixed cost base (rent, service staff) intended to serve dine-in customers, but in pivoting towards a greater mix of delivery orders, these fixed costs remain, without generating the dine-in sales for which they were intended. Merchants who follow a hybrid model of online and offline sales channels will need to find efficiency gains that can protect profitability and make their business sustainable.

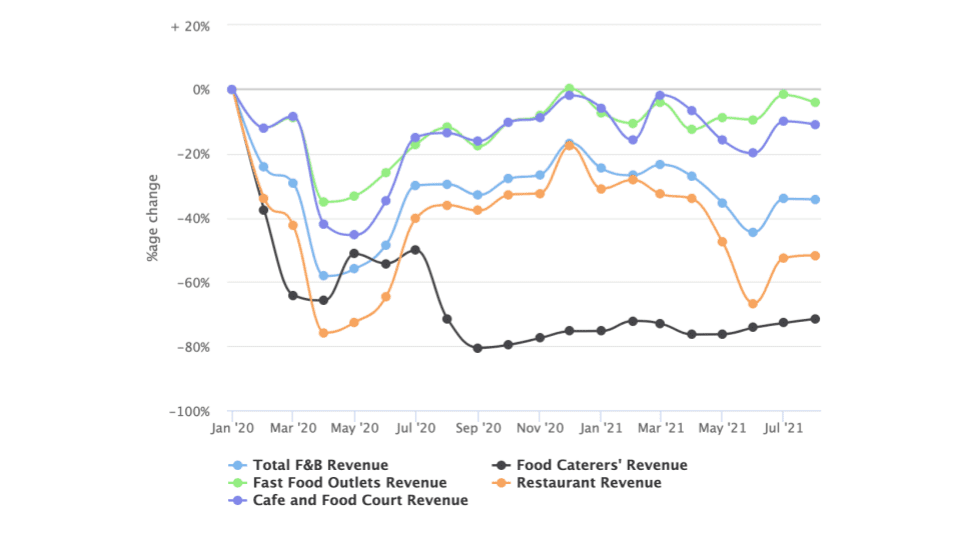

Not all merchants perform the same

Some food businesses have weathered the pandemic better than others; evidence from Singapore suggests that merchants with business models conducive to a flexible, scalable, cost-controlling approach are better adapted to weathering shocks: for example as of August 2021, fast food merchants have recovered in terms of sales almost to pre-pandemic levels in Singapore, due to their convenience and ease of access, but also possibly due to supply chain/storage efficiencies. In contrast, even as the pandemic saw a surge in new food delivery consumers in Singapore1, revenues for restaurants are still less than half of their pre-pandemic levels.

This uneven recovery is worrying as it is in the interest of everyone, from consumers to merchants to delivery platforms, to foster a vibrant and diverse food market, in which all food merchants are equipped to survive and flourish.

Figure 3: Change in revenue for different types of Food and Beverage merchants over time. Source: Graph from Singapore Department of Statistics.

New and more resilient business models could be a viable way forward

It is therefore more important than ever to better understand and address the fundamental issues in the industry, in order to ensure that all food merchants can get the most out of both online and offline opportunities and build resilient, growth-oriented business models able to withstand future shocks on the scale of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Should merchants be rethinking what it means to expand their operations–away from acquiring more physical space to shared space schemes able to save big on fixed costs? Could the cloud kitchen model, rapidly gaining popularity in the region, be a model to look to? Some evidence suggests that merchants able to assimilate this model benefit from reduced fixed and variable costs, and are able to scale their businesses more efficiently.

Grab is committed to better understanding the barriers that food merchants face in the region, and to support the region’s businesses to harness new business models to thrive and be more resilient to Covid or whatever shocks may come next on Southeast Asia’s road to growth.

Cover photo credit: https://unsplash.com/@christianchen

1 Euromonitor International Survey, 2021